It’s

fair to say that Inter have had better sts to the season. Although

they qualified from the Champions League group stage with a game to

spare, they currently languish in 16th place in Serie A.

Admittedly they have a game in hand, but they are still a colossal 14

points behind league leaders Juventus with a third of the season gone.

The triumphant 2009/10 season when the nerazzurri became the first Italian team to win the treble of the scudetto, the Coppa Italia

and the Champions League in a single year under the guidance of José

Mourinho seems a distant memory. Inter fans have become accustomed to

success, as that triumph meant that their team had won five league

titles in a row (including the one awarded to them for 2005/06 by the

courts after the calciopoli scandal).

There

are many reasons behind this decline, not least an aging squad, but

most of the problems are off the pitch. The board’s lack of a long-term

strategy is evidenced by the rapid turnover in coaches since the

“special one” moved to Real Madrid in the summer of 2010. Rafael

Benitez’s miserable six-month reign did not reach Christmas, while past

Brazilian international Leonardo lasted little longer, as he joined

Paris Saint-Germain in June 2011.

His

replacement, the former Genoa boss Gian Piero Gasperini, fared no

better, as he was unceremoniously sacked after four defeats in five

games, notable only for a plethora of formations that confused his own

team rather more than the opposition. The current incumbent, Claudio

Ranieri, brings vast experience to the role, but he is Inter’s fifth

manager in less than two years.

"Should I stay or should I go?"

The

club’s confusion is further highlighted by the names of the other

managers that they approached for the position, including the likes of

Fabio Capello, Guus Hiddink, André Villas-Boas and Marcelo Bielsa. If

you can discern any similarities in their tactical approaches, then

you’re a better man than me. Unsurprisingly, they all rejected the

poisoned chalice.

The

other explanation for Inter’s woes is financial, namely that the club

no longer splashes out the vast sums on recruiting players that it has

done in the past. Their modus operandi

under long-serving president Massimo Moratti has been to run the

business at a huge loss ever year, which has only been made possible by

the owner covering the deficit with continual capital injections.

In

fact, in the 16 years since Moratti took over, the club has accumulated

losses of around €1.3 billion with the president personally putting in

over €750 million. Moratti has been criticised by many Inter fans, but

he can hardly be accused of not putting his money where his mouth is.

Even if his decisions have not always been the best, the reality is that

the president’s financial support has been an absolutely essential part

of the club’s success.

However,

this approach will not work in the future, as Inter are faced with the

new challenge of UEFA’s Financial Fair Play (FFP) Regulations, which

will ultimately exclude from European competitions those clubs that fail

to live within their means, i.e. make a profit.

The

first season that UEFA will start monitoring clubs’ financials is

2013/14, but this will take into account losses made in the two

preceding years, namely 2011/12 and 2012/13, so Inter’s accounts need to

rapidly improve.

However,

they don’t need to be absolutely perfect, as wealthy owners will be

allowed to absorb aggregate losses (“acceptable deviations”) of €45

million, initially over two years and then over a three-year monitoring

period, as long as they are willing to cover the deficit by making

equity contributions. The maximum permitted loss then falls to €30

million from 2015/16 and will be further reduced from 2018/19 (to an

unspecified amount).

This

effectively means that Inter need to slash their spending, especially

transfer fees and wages. Although the new rules have destroyed Inter’s

traditional business model, they were initially welcomed by Moratti,

”Some thought that FFP was against owners like me, but I say that at

last it means that I can stop putting money into football every day.

Inter are so expensive that I wouldn’t recommend it to anyone. I hope

that FFP allows us to experience football in a different way.”

The

impact on Inter’s activity in the transfer market has been dramatic. In

the 12 years up to the end of the 2009 season, their net spend was €473

million (with staggering gross spend of €831 million), while the last

three seasons has seen net sales of €24 million. Even when Mourinho

spent big on the likes of Samuel Eto’o, Diego Milito and Wesley

Sneijder, this was more than covered by the amazing fee received from

Barcelona for Zlatan Ibrahimovic.

The

new regime was explained this summer by chief executive officer Ernesto

Paolillo, “We have to sell, then after we have sold we will see what

Inter will buy. Absolutely, we are thinking of FFP.” His views were

echoed by sporting director Marco Branca, when explaining that the club

could no longer afford the fees commanded for top talent like Alexis

Sanchez, “We have to organise our finances for the financial fair play

rules in the next two years. We are looking for younger players now with

great talent, who we can develop.”

That

policy has meant the arrival of youngsters like Ricardo Alvarez, Yuto

Nagatomo and Philippe Coutinho, but the reluctance to spend also

contributed to the departure of Rafael Benitez, who had issued the club

with a “back me or sack me” threat.

This belt tightening is clearly evident when looking at the net spend in Serie A

over the last three seasons with Inter’s net sales of €24 million only

exceeded by Udinese, a famous selling club. Although it is true that

most clubs have reduced their transfer expenditure, it is noticeable

that in the same period two of Inter’s main rivals, Juventus and Napoli,

lead the way with over €100 million apiece. Juventus currently lead the

league, while Napoli are going great guns in the Champions League…

Of

course, that is the downside of turning the taps off, as there is a

good chance that the team will become less competitive, at least in the

short-term. There has clearly been a diminution in Inter’s offensive

capacity with Ibra and Eto’o (21 goals in Serie A

last season) being followed by Mauro Zarate and Diego Forlan,

especially as the Uruguayan is ineligible for the Champions League group

stages.

The

fundamental reason that the club needs to address its finances is, of

course, its massive losses. Over the last five years, these have

amounted to a shocking €665 million. Eat your heart out, Manchester

City. A couple of years ago, Moratti attempted to explain this, “The

considerable loss is justified to keep our team at the top level

worldwide.” In other words, it’s the price of success.

There

are a couple of ways of looking at the trend. On the one hand, the

losses have been largely reducing since the €207 million reported in

2007, but on the other hand there was certainly plenty of room for

improvement. The best result in recent years was the €69 million loss in

2010, though that was heavily influenced by the Champions League

success and the sale of Ibrahimovic.

What

is quite worrying is the deterioration last season to an €87 million

loss, especially as the word on the street was that the deficit would be

“only” €60 million, thus raising grave concerns that the plan to be in

line with FFP was already in tatters.

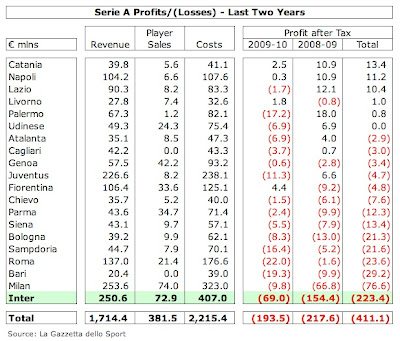

Of

course, Inter are by no means alone among Italian teams in making

losses. If we look at a schedule of the profit and loss accounts of Serie A

teams over the last two (fully reported) seasons, it’s a sea of red ink

with only six clubs profitable over that period. However, it’s the

magnitude of Inter’s losses that is striking with the club recording the

largest losses in each of those seasons. Their cumulative loss of €223

million was far higher than the next worst club, Milan with €77 million.

The

other negative point to note is Inter’s high reliance on player sales.

In fact, if we exclude profit from this activity plus the largely

positive impact of exceptional items, then the situation becomes even

more stark, as the underlying loss has averaged around €150 million over

the last four years.

Profit

on player sales was worth an impressive €72 million in 2010 (largely

Ibrahimovic €54 million, Biabiany to Parma €5 million and Maxwell to

Barcelona €4 million) and a net €31 million in 2011 (mainly Balotelli to

Manchester City €22 million, Burdisso to Roma €8 million and Destro to

Genoa €5 million). The latter sum would have been even higher if Inter

had not had to write-off an incredible €21 million on some player sales,

notably Quaresma to Besiktas (€13 million) and Mancini to Atletico

Mineiro (€5 million).

Both

2006 and 2007 were adversely impacted by a change in the accounting

treatment for the amortisation of transfer fees, while 2006 was boosted

by the sale of Inter’s brand to a subsidiary. In the last couple of

years, profits have been enhanced by €16 million compensation paid by

Real Madrid to secure Mourinho’s services and a €13 million payment by

RAI for the right to use the image library.

It’s

not as if Inter’s revenue is too shabby. In fact, for 2009/10 (the last

season when all Italian clubs have published their accounts), their

revenue of €225 million was the largest in Serie A with only

Milan and Juventus anywhere near them. Roma were the only other club

with revenue above €100 million, while the others were miles behind the nerazzurri.

Inter’s

revenue also places them 9th in Deloitte’s European Money League, which

on the face of it is pretty good, though problems begin to emerge when

we take a closer look, as they are a long way short of their peers

abroad. Real Madrid and Barcelona, generate around €400 million, which

is around twice as much as Inter. As well as benefiting from substantial

individual TV deals, the Spanish giants are also allowed to count

membership fees as income (instead of capital increases).

Both

Manchester United and Bayer Munich earn around €100 million more, the

English taking advantage of significantly higher match day revenue,

while the Germans’ commercial expertise puts Inter to shame. This vast

revenue discrepancy makes it difficult to compete, especially when that

shortfall in turnover occurs every year.

Those

of you who take a keen interest in football finances may be wondering

why the revenue figures used in the Money League are lower than those

reported in Italy. The reason for the difference is that Italian

accounts report gross revenue, while Deloitte uses net income, as this

is consistent with the approach used in other countries. Therefore, for

2009/10 this excludes the following: (a) gate receipts given to visiting

clubs €3 million; (b) TV income given to visiting clubs €18.4 million;

(c) revenue from player loans €1.1 million; (d) change in asset values

€3.4 million. Adding the €25.8 million adjustments to the €224.8 million

in my analysis gives the €250.6 million reported in Italy.

Inter’s

challenge is made all the more difficult by the underlying problems in

Italian football. This year a report form the Italian Football

Federation (FIGC) concluded, “The current business model is difficult to

sustain and not very competitive.” Its president, Giancarlo Abate,

noted that in particular match day income, sponsorships and

merchandising were in need of urgent attention to reduce the reliance on

TV money.

Ten years ago the total revenue of clubs in Serie A of €0.9 billion was only just behind the Premier League’s €1.1 billion and practically double the other major leagues (Bundesliga, La Liga and Ligue 1),

who all earned around €0.5 billion. Last year, the picture looked very

different with the Premier League’s revenue surging to €2.4 billion,

while the Bundesliga and La Liga had both caught up with Serie A at €1.5 billion with Ligue 1 trailing at €1.2 billion.

This

is reflected in the revenue growth of leading European clubs. Although

Inter’s growth looks pretty good against other Italian teams, it pales

into insignificance compared to top teams in Spain, England and Germany.

Two examples will illustrate that: first, Arsenal’s revenue in 2005 was

€28 million less than Inter’s, but is now €48 million more; second,

Barcelona’s revenue was only €47 million higher six years ago, so just

about within striking distance, but is now far over the horizon at €234

million higher. As Milan’s CEO, Adriano Galliani said, “Twenty years ago

Milan invoiced more than Real Madrid, today only half. That’s the real

problem.”

Overall,

Inter’s revenue has only grown by 13% in the last five years from €188

million to €213 million. Like all the big Italian clubs, the majority of

Inter’s revenue (59%) comes from television with €124 million.

According to the FIGC report, Serie A

has the highest dependency on TV income of any of the leading five

leagues at 65%, compared to France 60%, England 50%, Spain 38% and

Germany 32%.

The

flaws in Inter’s business model are clear with only 25% generated by

commercial operations (€54 million) and 15% from match day (€33

million). In the last two years, these last two revenue streams have

barely increased at all and only television has contributed any

meaningful growth, largely due to a more lucrative Champions League

contract.

In

2009/10, Inter earned an impressive €138 million from television, which

was the highest in Italy, thanks to a combination of an attractive

domestic individual deal and those Champions League millions. Only

Juventus and Milan were in the same ballpark (for identical reasons),

while all other Italian clubs received considerably less money, e.g.

Napoli, Lazio and Fiorentina got less than half those sums at around €40

million.

Years

of protest at this lack of a level playing field finally led to a new

collective agreement being implemented at the beginning of last season.

There is a complicated distribution formula, which still favours the

bigger clubs, though the result is a small reduction at the top end.

Under the new regulations, 40% will be divided equally among the Serie A

clubs; 30% is based on past results (5% last season, 15% last 5 years,

10% from 1946 to the sixth season before last); and 30% is based on the

population of the club’s city (5%) and the number of fans (25%).

So,

the larger clubs will lose out from the new arrangement, but mid-tier

clubs should benefit. There has been much discussion over how the number

of fans (worth 25% of the deal) will be calculated, leading to a major

dispute between the larger clubs and the smaller clubs, but this now

looks to have been resolved.

An article in La Repubblica

suggested that Inter would lose €8 million, but the reduction reported

in the accounts is far smaller with the domestic TV money falling just

€3 million from €89 million to €86 million, though it is not clear

whether this is a final figure or just an estimate while negotiations

continued.

One

reason that the decrease might be lower than anticipated is that the

total money guaranteed in the new collective deal by media rights

partner Infront Sports is approximately 20% higher than before at

around €1 billion a year, which cements Italy’s position as the second

highest TV rights deal in Europe, only behind the Premier League, but

significantly ahead of Ligue 1 and La Liga. In fact, Italy’s deal is worth twice as much as the Bundesliga.

That’s

particularly impressive, given how little is received for foreign

rights, though there is some optimism that this will increase in the

next round of contract negotiations. On the other hand, it is not

completely clear what will happen with the 2013-15 deal for domestic

rights. Although €2.5 billion has been secured from Sky/RTI for 12 of

the 20 Serie A clubs, the league is still to determine how to handle rights for the eight clubs not included.

Somewhat

puzzlingly, I can find no trace in Inter’s accounts of prize money for

the UEFA Super Cup (runners-up €1.2 million) and the FIFA Club World Cup

(winners $5 million) that were both disputed in 2010, so it might be

the case that this money will only be booked in the 2011/12 accounts.

The

Champions League has been kind to Inter financially with over €115

million received in the last three years in participation and prize

money alone, though Europe’s flagship competition can be something of a

double-edged sword, as their revenue declined by €11 million in 2011

from €49 million to €38 million, due to Inter only reaching the

quarter-finals compared to winning the trophy the previous season. Those

are just the television distributions, but there are also be additional

gate receipts and bonus clauses in various sponsorship deals.

The

Europa League's TV distribution is very low in comparison, so last

season the four Italian representatives only earned around €2 million

each. Although none of them progressed further than the last 32, the

highest pay-out was still only €9 million. However, at least this

tournament still delivers additional gate receipts.

One

glaring weakness for Inter is match day revenue, which is very low at

€33 million, down from €39 million the previous year, largely due to a

reduction in Champions League gate receipts from €17 million to €7

million.

Although

this is the highest in Italy, it is tiny compared to leading clubs

abroad. This is perhaps best illustrated by a comparison with Manchester

United and Arsenal, who earn €126 million and €108 million

respectively. This works out to around €4 million revenue a match, which

is over three times as much as Inter (€1.3 million), even though their

stadiums are smaller.

Inter’s

average attendance of 58,000 in 2010/11 is impressive (again the

highest in Italy) and was actually the eighth best in Europe, but San Siro suffers from having hardly any premium seats or corporate boxes, which are the money spinners elsewhere.

This

is why Inter have been exploring opportunities for moving to a new

stadium that could maximise their revenue earning potential, including

naming rights, as explained by Paolillo, “In Europe the stadium makes

money seven days out of seven.” Not only that, but Inter have to pay

€4.3 million rent a year to the local council, who own the stadium.

Unfortunately

for Italian clubs, Italy failed in their bids to host either the 2012

or 2016 Euros, which would have been a catalyst to upgrade. Juventus are

the only top club that owns its own stadium, which they hope will

double their match day income. Even that project was beset with

bureaucratic delays, which is why Paolillo hopes that new laws will be

introduced to facilitate the construction of new stadiums. Patience will

still be required, as Moratti recently explained that it would not be

possible to move “in the short-term”.

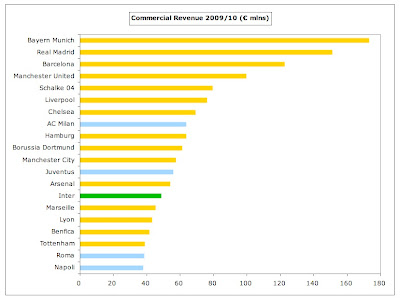

Even

after a €6 million rise in commercial revenue in 2011 from €48 million

to €54 million, this is still fairly low for a club of Inter’s history.

Perhaps understandably it’s less than Milan and Juventus, but it’s only

just higher than Roma and Napoli. More pertinently, it’s significantly

lower than Bayern Munich, who earn an astonishing €173 million.

Inter

have enjoyed very long-term relationships with commercial partners, but

this may have prevented them from taking up more lucrative

opportunities elsewhere. Pirelli have been Inter’s shirt sponsor since

1995, but only pay €12 million a year. Similarly, kit supplier Nike have

been partners since 1998, also paying €12 million a year.

To

be fair, this compares favourably with deals at other Italian clubs:

(a) shirt sponsors: Milan – Emirates €12 million, Juventus – BetClic €8

million, Napoli – Lete €5.5 million and Roma – Wind €5 million; (b) kit

suppliers: Milan – Adidas €13 million, Juventus – Nike €12 million, Roma

– Kappa €5 million and Napoli – Macron €4.7 million.

The

issue is that these deals are much lower than leading clubs abroad. For

example, the following clubs all have shirt sponsorships worth more

than €20 million a season: Barcelona, Bayern Munich, Manchester United,

Liverpool, Manchester City and Real Madrid.

Belatedly,

they are looking to make more from global opportunities, hence playing

the Italian Super Cup match against Milan in the Bird’s Nest stadium in

Beijing, but they have a lot of ground to make up.

The

other factor damaging Inter is one facing all Italian clubs, namely a

problem with fake merchandising. They can seemingly do little to prevent

this, but have asked the state to tackle the issue. That’s a generic

issue, but one specific to Inter is the annual €16 million payment for

use of the brand after the earlier operation to sell this to one of its

subsidiaries.

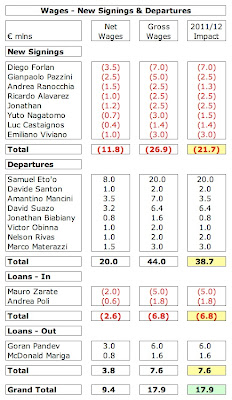

However,

the most important challenge for Inter is their wage bill. The good

news is that they managed to cut this by €44 million in 2011 from a

frightening €234 million to €190 million, thus reducing the important

wages to turnover ratio from 104% to 89%, so it now comprises player

salaries €149 million, coaching staff €16 million, bonus payments €13

million, other staff €6 million and social security €6 million.

On

the face of it, this is a notable achievement, but it masks some

worrying factors. The main reasons for the decrease were a €38 million

cut in bonuses, due to the Champions League payments the prior year, and

a €9 million reduction in coaching salaries, following the departure of

Mourinho. The player salaries actually rose by €3 million, which was

not in the plans, probably due to the number of “senior citizens” still

on the books.

In

addition, this is still a very high wage bill by anybody’s standards.

As a comparison, it’s only €10 million below big-spending Manchester

City’s €200 million (the highest wage bill ever reported by an English

club). It’s also more than a third higher than the €142 million paid by

Inter as recently as 2006.

Furthermore,

it remains one of the largest wage bills in Italy, e.g. in 2009/10

Inter’s wages were about the same as Juventus and Roma combined. An

analysis by La Gazzetta dello Sport

this summer suggested that Milan had overtaken Inter in the wages

stakes (at least for the first team squad) with €160 million compared to

€145 million, but it’s far from certain that their figures are

accurate. In any case, a wage to turnover ratio of just under 90% is

nothing to write home about and is much worse than UEFA’s recommended

maximum limit of 70%.

The

other element of player costs, namely amortisation has also been

reduced in 2011 from €61 million to €53 million, though it is still two

thirds higher than it was in 2008, and is higher than other leading

Italian clubs with Milan, Juventus and Napoli the closest at around €40

million.

For

non-accountants, amortisation is the annual cost of writing-down a

player’s purchase price, e.g. Gianpaolo Pazzini was signed for €19

million on a 4½ year contract, but his transfer is only reflected in the

profit and loss account via amortisation, which is booked evenly over

the life of his contract, i.e. €4.2 million a year (€19 million divided

by 4.5 years).

"Old man river keeps rolling along"

Despite

Inter’s history of large losses, they have publicly welcomed FFP.

Paolillo said that the initiative was the right one for the football

industry in order to avoid the collapse of clubs, likening the state of

the sport’s finances to the sub-prime banking crisis. More specifically,

he added that Inter was up for the fight, “We will be ready to meet all

the standards set by UEFA and we are working on various fronts. That

means cutting costs and increasing revenues.”

All

of the losses made to date are not considered for FFP, as the first

accounts to be included in the calculation are those for 2011/12. Inter

seem quite optimistic about their ability to meet the targets with talk

of reducing the loss to €30 million this season and reaching break-even

in two years, which would be within UEFA’s acceptable deviation of €45

million for the first two years.

However,

that is by no means a done deal, especially as Inter’s track record for

financial planning is not the best, as seen by last year’s figures

where the loss widened to €87 million, much worse than the forecast

improvement to €60 million.

"Me and Julio down by the school yard"

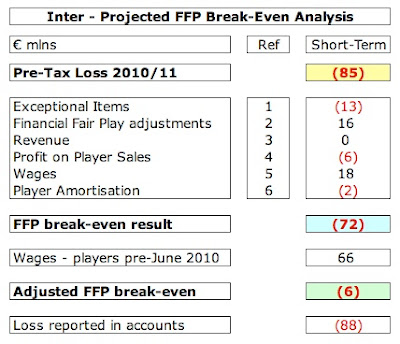

So

let’s try to project Inter’s loss for 2011/12, based on the information

we already have. This is accompanied by a health warning that this type

of analysis will never be 100% accurate, as some of the reported

figures are not certain, e.g. transfer fees, wages and contract

extensions. Nevertheless this exercise should give us a strong

indication of whether Inter are at all close to achieving their

objectives.

1. Exceptional Items

By

definition, the 2010/11 once-off €13 million payment for use of the

image archive should not be repeated every year, so this should be

excluded.

2. Financial Fair Play Adjustments

It

is not generally appreciated that UEFA’s break-even calculation is not

the same as a club’s statutory accounts, as it excludes certain expenses

that are considered to represent positive investment, such as

expenditure on youth development (€10 million) and community (€2

million) plus depreciation on tangible fixed assets (€4 million), which

gives a total of €16 million to be deducted.

Youth

development and community investment are not separately disclosed in

the accounts, so these values are estimates based on similar reviews of

other clubs.

"Two Diegos for the price of one"

3. Revenue

Even

though there is much potential for growing revenue in the long-term,

Inter have limited scope for increases next year. Nothing will happen on

the stadium front, the TV deal is unchanged and the club is locked in

to its main sponsorship agreements. The only wild card is how far Inter

progress in the Champions League – though there is also the issue of

what happened to the €5 million revenue from the UEFA Super Cup and the

FIFA Club World Cup.

All in all, I have assumed that revenue remains flat.

4. Profit on Player Sales

The

post-balance sheet events section in Inter’s accounts inform us that

they have already made €25 million profit on player sales, largely due

to Eto’o going to Anzi Makhachkala and Davide Santon to Newcastle

United. Unless further sales are made in the January transfer window,

this means a €6 million reduction year-on-year, as 2010/11 included €31

million profit here.

The

problem for Inter is that they would need to maintain this level of

player sales each year (unless they can compensate for €25 million

elsewhere), so their fans can expect at least one star, such as

Sneijder, Maicon or Julio Cesar, to be sold next summer. Indeed,

Sneijder has already admitted, “Inter need money and I’m for sale if the

right offer comes in.”

Of

course, a strategy of “selling the family silver” is finite (and

potentially counter-productive), unless Inter acquire an ability to

develop players for sale, maybe through their academy. What’s for sure

is that Inter will never repeat the mega profits made from the

Ibrahimovic coup.

5. Wages

Inter

are attacking their wage bill on a number of fronts: (a) a “salary cap”

of €3 million for a first team player, unless he is a superstar; (b)

the future remuneration package will have a lower basic salary with a

higher bonus element geared to success; (c) contracts for older players

will extended at a lower salary; (d) expensive, fringe players will be

offloaded when possible, e.g. Sulley Muntari; (e) high earners like

Eto’o, Mancini and Suazo will be allowed to leave; (f) and replaced with

younger, cheaper players.

This

all sounds very logical, though some strange decisions have still been

taken, such as the recent contract extension for Lucio, who has been a

great player, but whose best days are clearly behind him.

Using the salaries published in La Gazzetta,

the impact of new signings in 2011 is estimated to increase the wage

bill by €22 million. Note that Pazzini, Ranocchia and Nagatomo were all

recruited in January 2011, so the cost impact for 2011/12 is only six

months.

"Ricky, don't lose that number"

For the departures, I have taken the net salaries from La Gazzetta

and uplifted them by 50% to calculate the gross cost with the exception

of Eto’o whose cost has been widely reported as €20 million. That

produces savings of €39 million in 2011/12.

Similarly, the net impact of loan deals (Zarate and Poli in, Pandev and Mariga out) is a €1 million saving.

In total, the wage bill should come down by €18 million – though there will obviously also be the impact of Primavera moves, any new contracts and bonus payments.

There is talk of slashing the wage bill to around €120 million, but that is a long way off.

6. Player Amortisation

Although

the 2011 signings have relatively low salaries, they also increase the

costs via the amortisation of their transfer fees, which I have

estimated as €18 million per annum, though the impact in 2011/12 will be

only €14 million, due to some costs being booked last year for players

purchased in January.

The

€12 million forecast reduction in amortisation should be fairly

accurate, as these figures are taken directly from Inter’s accounts.

There is no improvement shown for some departures, as the players were

either home-grown (so no amortisation) or have been fully amortised in

the accounts, e.g. Marco Materazzi.

The

net impact is a small increase of €2 million, though I would expect

Inter’s frugal policy in the transfer market to eventually bear fruit,

leading to a sizeable reduction in a few years.

Adding

up all of the factors above (1 to 6) would produce a 2011/12 loss of

€88 million for Inter, though this falls to €72 million once the FFP

adjustments are excluded. Little wonder that Moratti warned, “We are not

yet able to balance the books. I don’t know how Italian clubs will play

in the Champions League in future, if UEFA’s fair play is confirmed.”

Looking

at the projected figures, his recent pessimism is perfectly

understandable, but there is a clause in the small print of the FFP

regulations (Annex XI) that states that clubs will not be sanctioned in

the first two monitoring periods, so long as: (a) the club is reporting a

positive trend in the annual break-even results; and (b) the aggregate

break-even deficit is only due to the 2011/12 deficit, which in turn is

due to player contracts undertaken prior to 1 June 2010.

In

other words, Inter would be allowed to exceed the “acceptable

deviation” of €45 million by the costs of pre-June 2010 signings, so

long as the 2011/12 deficit was only due to this factor.

Assuming

that this clause refers purely to wages (and does not include player

amortisation), I have calculated this exclusion for “big name” players

to be €66 million. Note that players whose contracts have been extended

since 1 June 2010 are not counted (as explicitly noted in the

regulations), so I have not included Milito, Zanetti, Sneijder and

Lucio.

This

would reduce the FFP result for the break-even calculation to just €6

million, which I am sure UEFA would look on favourably.

So

it seems that Inter’s old boys might have saved them once again.

Although this is a temporary factor, it does at least buy Inter more

time to get their house in order, though, as we have seen, that

effectively means more work (a lot more work) on the wage bill.

Of

course, the greatest threat to Inter’s bottom line next year is if they

fail to qualify for the Champions League (for the first time in 10

years). Given their awful start, that is no longer a formality,

especially as Italy now only has three places following the loss of one

to Germany this season, though it should be remembered that their form

in the second half of last season was superlative and they should be

helped by the return of some of their stars from injury.

"King Money"

Some

have suggested that UEFA would never apply the ultimate sanction of

throwing a leading club out of their competitions, but Moratti is not so

sure, “I do believe they will go ahead with it, so you can’t pretend

it’s not happening.” His view are supported by UEFA’s General Secretary,

Gianni Infantino, “We will apply these rules strictly in order to

safeguard the future of our game.”

In

the meantime, Inter are pushing ahead with their plans, including a

focus on youth, not just in terms of buying less experienced players,

but also their own academy. Even if their youngsters do not progress to

the first team, they can be sold profitably or used as makeweights in

deals, as Biabiany was when buying Pazzini from Sampdoria.

From

the perspective of FFP, it would make little sense for Moratti to step

aside, as benefactors are no longer allowed to support losses by putting

in money. That said, it is possible that a Sheikh or Russian

billionaire might be better placed to secure “friendly” sponsorship

deals, as Manchester City have done with Etihad.

For

the time being, it looks like Inter will have to continue on their path

of austerity, echoing the philosophy of the new Italian government. In

truth, they are caught between a rock and a hard place, as they need to

rapidly cut costs, but at the same time their squad is in urgent need of

rejuvenation. It’s a tricky problem, but they somehow need to resolve

it if they wish to once again compete at the highest levels.

Source: http://swissramble.blogspot.com/search/label/Inter

Source: http://swissramble.blogspot.com/search/label/Inter

No comments:

Post a Comment